I Hear My People, But I Don’t See My People

A contemporary example of fluid identity and liberation through hybridity can be seen in the global circulation of Korean pop music, or K-pop. Many Korean idols who pursue hip-hop and rap-aligned sounds adopt stylistic elements rooted in African American culture, including African American Vernacular English, fashion, and choreography. This blending challenges boundaries of race, nation, and authenticity. Identity in this context becomes something performed and assembled from cultural fragments rather than fixed to biology or ethnicity. As a result, K-pop demonstrates how identities can be constructed through crossing boundaries, while also exposing tensions between representation and lived experience.

Hybridity on the Global Stage

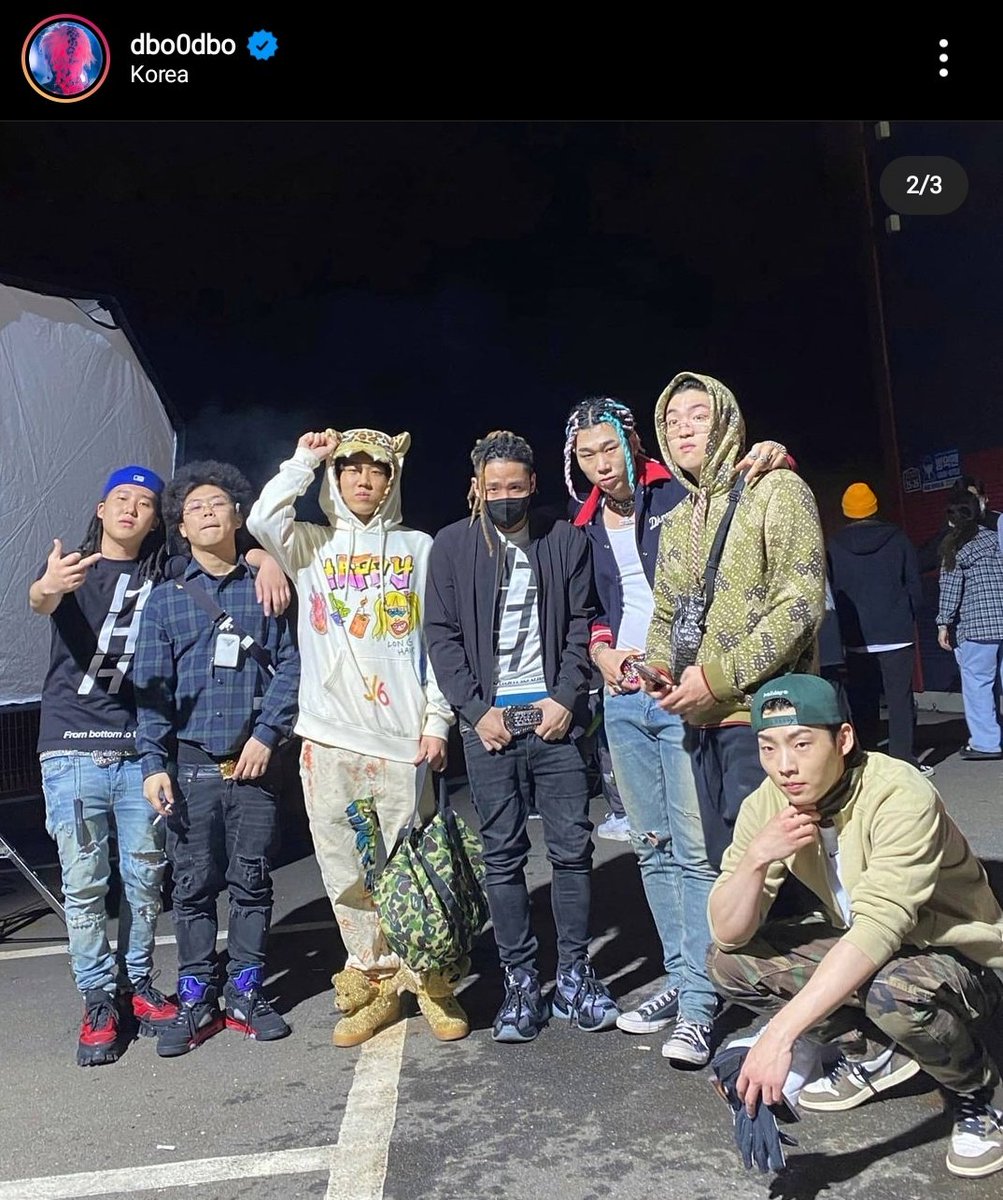

The history of Black cultural borrowing in K-pop is well documented. As O. Gaines argues in The Tufts Daily, “Black culture has heavily influenced K-pop’s music, fashion and overall aesthetic since its inception,” yet that influence often goes uncredited or is misunderstood as neutral globalization rather than racialized borrowing. This pattern is not new. In the 1990s, J. Y. Park, founder of JYP Entertainment, performed in blackface alongside background dancers, a moment that revealed how Blackness could be treated as costume within the industry’s early formation. Decades later, Park again received criticism for posting a remix of DNA by Kendrick Lamar, featuring non-Black performers styled with afros and dreadlocks. In these instances, Black cultural aesthetics function as wearable signifiers layered onto Korean bodies.

Image: Screenshot from J. Y. Park’s Kendrick Lamar remix performance, originally shared by @CallMeGizzzy on X (formerly Twitter), [June 14, 2021]. Used for commentary and educational purposes.

K-pop artists construct hybrid identities by performing Black musical and aesthetic traditions alongside Korean language and culture, creating fluid identities that cross racial and national boundaries. Groups like BTS incorporate hip-hop choreography, rap flows, and streetwear aesthetics rooted in Black American culture into their global pop identities. This challenges racial boundaries by staging Black cultural forms through non-Black artists, national boundaries by translating African American genres into Korean contexts, and linguistic boundaries by blending Korean and English in rap and pop lyrics. It also destabilizes authenticity boundaries, presenting identity as performance rather than essence.

At the same time, hybridity in K-pop does not only function as appropriation. It also creates new transnational spaces of belonging. In her thesis on fandom and identity, Varma explains that K-pop communities allow fans to “negotiate identity and belonging across national and racial lines,” producing forms of attachment that are not confined to geography or ethnicity. This reflects the liberatory potential of hybridity: identities are no longer anchored solely in nation or race but are assembled through shared media, aesthetics, and affective communities.

This phenomenon closely echoes the theory advanced in A Cyborg Manifesto by Donna Haraway, who argues that identities are hybrid assemblages rather than pure categories. K-pop artists function like cultural cyborgs, assembling identities from multiple systems such as Korean tradition, Black American music, global capitalism, and digital media networks. However, while Haraway celebrates hybridity as boundary-breaking and potentially liberating, K-pop demonstrates that hybridity can also reproduce unequal cultural exchange when certain identities carry historical oppression.

The work of Janelle Monáe offers a revealing contrast. Through Afrofuturist performance, Monáe uses hybridity to center Black identity and reclaim agency. In contrast, K-pop often circulates Blackness globally as a performable identity layer signaling coolness and authenticity. Monáe mobilizes hybridity as resistance from within Black experience, while K-pop illustrates how Blackness can become a globally consumable aesthetic detached from lived history.

The Future of Wearable Identity

Looking ahead 20–30 years, identity may become even more modular and technologically mediated. The rise of AI-generated performers and virtual idols suggests that artists may soon construct personas that are partially human and partially algorithmic. If hybridity already allows cultural identities to be assembled and worn, future technologies may allow identities to be coded, customized, and projected across virtual environments. This could expand freedom of self-expression and create new forms of solidarity across borders. Yet it will likely intensify debates about ownership, authenticity, and historical accountability.

AI Attestation: The AI ChatGPT was utilized to plan and edit this posting. https://chatgpt.com/share/699b4620-def4-8009-9ff7-6e16afa28e35

Citations

Gaines, O. (2022, March 16). K-Weekly: Black appropriation in K-pop (Part 1). The Tufts Daily. https://www.tuftsdaily.com/article/2022/03/k-weekly-black-appropriation-in-k-pop-part-1

Varma, T. (2024). IDENTITY AND BELONGING Identity and Belonging: South Asian Americans Navigating K-pop Industry and Fandom. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/commmediathesisprogram/wp-content/uploads/sites/1393/2025/01/VARMA-2023.pdf